Which Is One Of The Greatest Changes That Took Place During The Middle Kingdom?

| Eye Kingdom of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| around 2055 BC – around 1650 BC | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Thebes, Itjtawy | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian | ||||||||

| Religion | Aboriginal Egyptian organized religion | ||||||||

| Government | Divine, absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||

| • around 2061 – around 2010 BC | Mentuhotep 2 (first) | ||||||||

| • around 1650 BC | Last king depends on the scholar: Merneferre Ay or the last king of the 13th Dynasty | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| • Established | effectually 2055 BC | ||||||||

| • Disestablished | around 1650 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today function of | Egypt Sudan | ||||||||

The Eye Kingdom of Egypt (also known every bit The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of aboriginal Egypt following a menstruation of political division known equally the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from approximately 2040 to 1782 BC, stretching from the reunification of Egypt under the reign of Mentuhotep Two in the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. The kings of the Eleventh Dynasty ruled from Thebes and the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty ruled from el-Lisht.

The concept of the Center Kingdom equally ane of iii gold ages was coined in 1845 by High german Egyptologist Baron von Bunsen, and its definition evolved significantly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.[1] Some scholars likewise include the Thirteenth Dynasty of Egypt wholly into this flow, in which instance the Middle Kingdom would terminate around 1650 BC, while others merely include it until Merneferre Ay around 1700 BC, final rex of this dynasty to exist attested in both Upper and Lower Egypt. During the Middle Kingdom period, Osiris became the most important deity in popular religion.[2] The Middle Kingdom was followed by the Second Intermediate Menses of Egypt, another menstruum of sectionalization that involved foreign dominion of Lower Egypt by the Hyksos of Due west Asia.

Political history [edit]

Periods of ancient Egypt [edit]

Reunification under the Eleventh Dynasty [edit]

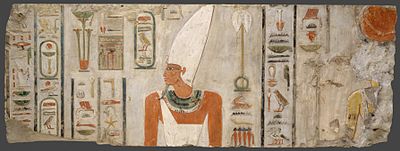

An Osiride statue of the commencement pharaoh of the Centre Kingdom, Mentuhotep II

Afterward the plummet of the Old Kingdom, Egypt entered a period of weak pharaonic ability and decentralization called the Showtime Intermediate Period.[3] Towards the end of this menses, ii rival dynasties, known in Egyptology as the Tenth and Eleventh, fought for control of the entire state. The Theban Eleventh Dynasty just ruled southern Egypt from the Outset Cataract to the 10th Nome of Upper Arab republic of egypt. To the n, Lower Egypt was ruled by the rival Tenth Dynasty from Herakleopolis.[4] The struggle was to be ended by Mentuhotep II, who ascended the Theban throne in 2055 BC.[5] During Mentuhotep Two's fourteenth regnal yr, he took reward of a revolt in the Thinite Nome to launch an assault on Herakleopolis, which met little resistance.[four] After toppling the last rulers of the Tenth Dynasty, Mentuhotep began consolidating his power over all of Egypt, a process which he finished by his 39th regnal yr.[3] For this reason, Mentuhotep Two is regarded equally the founder of the Middle Kingdom.[6]

Mentuhotep II commanded petty campaigns south as far as the Second Cataract in Nubia, which had gained its independence during the First Intermediate Menses. He also restored Egyptian hegemony over the Sinai region, which had been lost to Egypt since the end of the Old Kingdom.[7] To consolidate his authorization, he restored the cult of the ruler, depicting himself as a god in his own lifetime, wearing the headdresses of Amun and Min.[viii] He died later on a reign of 51 years and passed the throne to his son, Mentuhotep III.[vii]

Mentuhotep III reigned for only twelve years, during which he continued consolidating Theban rule over the whole of Egypt, building a series of forts in the eastern Delta region to secure Egypt confronting threats from Asia.[seven] He also sent the starting time expedition to Punt during the Center Kingdom, using ships synthetic at the terminate of Wadi Hammamat, on the Ruddy Sea.[9] Mentuhotep III was succeeded past Mentuhotep Iv, whose proper name, significantly, is omitted from all ancient Egyptian king lists.[10] The Turin Papyrus claims that afterwards Mentuhotep 3 came "7 kingless years".[11] Despite this absence, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat that record expeditions to the Red Sea coast and to quarry rock for the royal monuments.[ten] The leader of this trek was his vizier Amenemhat, who is widely assumed to exist the futurity pharaoh Amenemhet I, the start king of the 12th Dynasty.[12] [thirteen]

Mentuhotep IV's absence from the rex lists has prompted the theory that Amenemhet I usurped his throne.[13] While there are no contemporary accounts of this struggle, certain circumstantial evidence may bespeak to the existence of a civil state of war at the end of the 11th Dynasty.[10] Inscriptions left by one Nehry, the Haty-a of Hermopolis, suggest that he was attacked at a place called Shedyet-sha by the forces of the reigning male monarch, but his forces prevailed. Khnumhotep I, an official under Amenemhet I, claims to have participated in a flotilla of twenty ships sent to pacify Upper Arab republic of egypt. Donald Redford has suggested these events should exist interpreted equally evidence of open war between two dynastic claimants.[14] What is certain is that, all the same he came to power, Amenemhet I was not of majestic birth.[xiii]

Twelfth Dynasty [edit]

Early on Twelfth Dynasty [edit]

The head of a statue of Senusret I.

A guardian statue which reflects the facial features of the reigning king, probably Amenemhat Ii or Senwosret II, and which functioned every bit a divine guardian for the imiut. Made of cedar wood and plaster c. 1919–1885 BC[15]

From the 12th Dynasty onwards, pharaohs oft kept well-trained standing armies, which included Nubian contingents. These formed the basis of larger forces that were raised for defense against invasion, or expeditions up the Nile or across the Sinai. However, the Eye Kingdom was basically defensive in its armed forces strategy, with fortifications congenital at the First Cataract of the Nile, in the Delta and across the Sinai Isthmus.[16]

Early in his reign, Amenemhet I was compelled to campaign in the Delta region, which had not received equally much attention as Upper Arab republic of egypt during the 11th Dynasty.[17] Also, he strengthened defenses betwixt Egypt and Asia, building the Walls of the Ruler in the E Delta region.[18] Perhaps in response to this perpetual unrest, Amenemhat I congenital a new capital for Arab republic of egypt in the due north, known equally Amenemhet It Tawy, or Amenemhet, Seizer of the Two Lands.[19] The location of this capital is unknown, but is presumably near the city's necropolis, the present-day el-Lisht.[20] Similar Mentuhotep II, Amenemhet bolstered his claim to authority with propaganda.[21] In item, the Prophecy of Neferty dates to near this time, which purports to be an oracle of an Old Kingdom priest, who predicts a rex, Amenemhet I, arising from the far due south of Egypt to restore the kingdom subsequently centuries of anarchy.[20]

Propaganda yet, Amenemhet never held the absolute power commanded in theory past the Old Kingdom pharaohs. During the Showtime Intermediate Flow, the governors of the nomes of Egypt, nomarchs, gained considerable power. Their posts had become hereditary, and some nomarchs entered into marriage alliances with the nomarchs of neighboring nomes.[22] To strengthen his position, Amenemhet required registration of land, modified nome borders, and appointed nomarchs straight when offices became vacant, just acquiesced to the nomarch arrangement, probably to placate the nomarchs who supported his rule.[23] This gave the Middle Kingdom a more than feudal organization than Egypt had before or would have after.[24]

In his twentieth regnal year, Amenemhat established his son Senusret I as his coregent,[24] beginning a practice which would be used repeatedly throughout the residue of the Middle Kingdom and once more during the New Kingdom. In Amenemhet's thirtieth regnal twelvemonth, he was presumably murdered in a palace conspiracy. Senusret, candidature against Libyan invaders, rushed home to Itjtawy to prevent a takeover of the government.[25] During his reign, Senusret connected the practice of directly appointing nomarchs,[26] and undercut the autonomy of local priesthoods past edifice at cult centers throughout Egypt.[27] Under his rule, Egyptian armies pushed s into Nubia as far equally the 2nd Cataract, building a edge fort at Buhen and incorporating all of Lower Nubia as an Egyptian colony.[28] Senusret I besides exercised control over the land of Kush, from the Second to the 3rd Cataract, including the island of Sai. The southernmost inscription containing Sesostris I's name has been constitute on the island of Argo, northward of modern Dongola.[29] To the west, he consolidated his ability over the Oases, and extended commercial contacts into Syrian arab republic-Palestine as far as Ugarit.[30] In his 43rd regnal year, Senusret appointed Amenemhet Ii as inferior coregent, before dying in his 46th.[31]

The reign of Amenemhat II has been often characterized as largely peaceful,[30] but records of his genut , or daybooks, take cast doubt on that assessment.[36] Among these records, preserved on temple walls at Tod and Memphis, are descriptions of peace treaties with sure Syrio-Palestinian cities, and military disharmonize with others.[36] To the south, Amenemhet sent a campaign through lower Nubia to inspect Wawat.[30] It does non appear that Amenemhet continued his predecessors' policy of appointing nomarchs, merely allow information technology become hereditary again.[26] Another expedition to Punt dates to his reign.[36] In his 33rd regnal yr, he appointed his son Senusret II coregent.[37]

Evidence for the military activity of whatsoever kind during the reign of Senusret Two is non-existent. Senusret instead appears to have focused on domestic issues, particularly the irrigation of the Faiyum. This multi-generational project aimed to convert the Faiyum haven into a productive swath of farmland.[38] Senusret eventually placed his pyramid at the site of el-Lahun, near the junction of the Nile and the Fayuum's major irrigation canal, the Bahr Yussef.[39] He reigned only fifteen years,[forty] which explains the incomplete nature of many of his constructions.[38] His son Senusret III succeeded him.

Acme of the Centre Kingdom [edit]

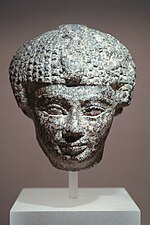

Statue head of Senusret Three

Senusret III was a warrior-male monarch, often taking to the field himself. In his 6th year, he re-dredged an Sometime Kingdom culvert around the Start Cataract to facilitate travel to Upper Nubia. He used this to launch a serial of brutal campaigns in Nubia in his 6th, eighth, tenth, and sixteenth years. After his victories, Senusret built a serial of massive forts throughout the land to found the formal boundary between Egyptian conquests and unconquered Nubia at Semna.[41] The personnel of these forts were charged to send frequent reports to the uppercase on the movements and activities of the local Medjay natives, some of which survive, revealing how tightly the Egyptians intended to control the southern edge.[42] Medjay were not allowed n of the border past send, nor could they enter by state with their flocks, only they were permitted to travel to local forts to merchandise.[43] Afterwards this, Senusret sent one more campaign in his 19th year, but turned back due to abnormally depression Nile levels, which endangered his ships.[41] I of Senusret's soldiers besides records a campaign into Palestine, perchance against Shechem, the only reference to a armed forces campaign against a sure location in Palestine from Middle Kingdom literature.[44](With other references to action confronting Asiatics.[45]) It is non known whether Arab republic of egypt wished to command Canaan like Northern Nubia, but numerous administrative seals of the menstruation accept been institute in that location, likewise equally other indications of increased activity North in this period.[46] [47] Byblos, known for its valuable wood, was probably an Egyptian dependency during this period.[48] [49]

Domestically, Senusret has been given credit for an administrative reform which put more power in the hands of appointees of the central government, instead of regional authorities.[41] Arab republic of egypt was divided into three water, or administrative divisions: Due north, S, and Caput of the South (perchance Lower Egypt, most of Upper Egypt, and the nomes of the original Theban kingdom during the war with Herakleopolis, respectively). Each region was administrated by a Reporter, Second Reporter, some kind of council (the Djadjat), and staff of minor officials and scribes.[52] The ability of the nomarchs seems to drop off permanently during his reign, which has been taken to indicate that the central regime had finally suppressed them, though there is no record that Senusret ever took directly action against them.[41]

Senusret Three left a lasting legacy equally a warrior pharaoh. His proper noun was Hellenized by later Greek historians every bit Sesostris, a proper noun which was then given to a conflation of Senusret and several New Kingdom warrior pharaohs.[53] In Nubia, Senusret was worshiped as a patron God by Egyptian settlers.[54] The duration of his reign remains something of an open up question. His son Amenemhet Three began reigning afterwards Senusret'southward 19th regnal twelvemonth, which has been widely considered Senusret's highest attested date.[55] All the same, a reference to a year 39 on a fragment found in the construction debris of Senusret'due south mortuary temple has suggested the possibility of a long coregency with his son.[56]

The reign of Amenemhat III was the height of the Center Kingdom's economic prosperity. His reign is remarkable for the degree to which Egypt exploited its resources. Mining camps in the Sinai, which had previously been used only by intermittent expeditions, were operated on a semi-permanent ground, equally evidenced by the construction of houses, walls, and fifty-fifty local cemeteries.[57] There are 25 separate references to mining expeditions in the Sinai, and iv to expeditions in Wadi Hammamat, one of which had over two grand workers.[58] Amenemhet reinforced his male parent's defenses in Nubia[59] and continued the Faiyum land reclamation projection.[60] Later on a reign of 45 years, Amenemhet Three was succeeded by Amenemhet Iv,[57] whose 9-year reign is poorly attested.[61] Conspicuously by this fourth dimension, dynastic ability had begun to weaken, for which several explanations accept been proposed. Contemporary records of the Nile flood levels bespeak that the finish of the reign of Amenemhet Iii was dry out, and crop failures may have helped to destabilize the dynasty.[60] Further, Amenemhet III had an inordinately long reign, which tends to create succession issues.[62] The latter statement perhaps explains why Amenemhet Four was succeeded past Sobekneferu, the first historically attested female king of Egypt.[62] Sobekneferu ruled no more than 4 years,[63] and as she apparently had no heirs, when she died the Twelfth Dynasty came to a sudden stop as did the Golden Age of the Heart Kingdom.

Turn down into the Second Intermediate Period [edit]

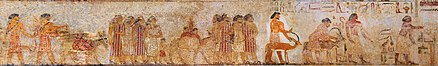

A kneeling statue of Sobekhotep V, 1 of the pharaohs from the declining years of the Centre Kingdom.

Later on the decease of Sobeknefru, the throne may have passed to Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep,[64] [65] though in older studies Wegaf, who had previously been the Cracking Overseer of Troops,[66] was thought to take reigned next.[67] Beginning with this reign, Egypt was ruled by a series of ephemeral kings for about ten to xv years.[68] Ancient Egyptian sources regard these equally the first kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty, though the term dynasty is misleading, every bit almost kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty were not related.[69] The names of these short-lived kings are attested on a few monuments and graffiti, and their succession lodge is merely known from the Turin Canon, although even this is not fully trusted.[68]

Afterward the initial dynastic chaos, a serial of longer reigning, better-attested kings ruled for well-nigh fifty to eighty years.[68] The strongest king of this period, Neferhotep I, ruled for eleven years and maintained constructive command of Upper Arab republic of egypt, Nubia, and the Delta,[70] with the possible exceptions of Xois and Avaris.[71] Neferhotep I was even recognized as the suzerain of the ruler of Byblos, indicating that the Thirteenth Dynasty was able to retain much of the power of the Twelfth Dynasty, at least up to his reign.[71] At some bespeak during the 13th Dynasty, Xois and Avaris began governing themselves,[71] the rulers of Xois being the Fourteenth Dynasty, and the Asiatic rulers of Avaris being the Hyksos of the Fifteenth Dynasty. According to Manetho, this latter defection occurred during the reign of Neferhotep's successor, Sobekhotep Four, though there is no archaeological evidence.[72] Sobekhotep IV was succeeded by the short reign of Sobekhotep V, who was followed by Wahibre Ibiau, so Merneferre Ai. Wahibre Ibiau ruled ten years, and Merneferre Ai ruled for twenty-iii years, the longest of whatever Thirteenth Dynasty king, simply neither of these two kings left equally many attestations equally either Neferhotep of Sobekhotep IV. Despite this, they both seem to accept held at least parts of Lower Egypt. After Merneferre Ai, however, no king left his name on whatsoever object found exterior the south.[73] This begins the final portion of the Thirteenth Dynasty when southern kings continue to reign over Upper Egypt. But when the unity of Egypt fully disintegrated, the Eye Kingdom gave mode to the Second Intermediate Period.[74]

Administration [edit]

When the Eleventh Dynasty reunified Arab republic of egypt it had to create a centralized administration such as had not existed in Egypt since the downfall of the Onetime Kingdom government. To do this, it appointed people to positions which had fallen out of utilize in the decentralized Commencement Intermediate Period. Highest among these was the vizier.[75] The vizier was the chief minister for the king, treatment all the day-to-day business of government in the king's identify.[75] This was a awe-inspiring chore, therefore it would often exist split into 2 positions, a vizier of the due north, and a vizier of the south. It is uncertain how often this occurred during the Middle Kingdom, only Senusret I clearly had two simultaneously operation viziers.[75] Other positions were inherited from the provincial form of regime at Thebes used by the Eleventh Dynasty earlier the reunification of Egypt.[76] The Overseer of Sealed Goods became the state's treasurer, and the Overseer of the Manor became the King's chief steward.[76] These three positions and the Scribe of the Royal Document, probably the king's personal scribe, appear to be the nearly important posts of the fundamental regime, judging by the monument count of those in these positions.[76]

Beside this, many Old Kingdom posts which had lost their original meaning and become mere honorifics were brought back into the key regime.[75] Simply loftier-ranking officials could claim the title Member of the Elite, which had been practical liberally during the First Intermediate Menses.[76]

This bones form of assistants connected throughout the Heart Kingdom, though at that place is some testify for a major reform of the cardinal government nether Senusret III. Records from his reign indicate that Upper and Lower Arab republic of egypt were divided into split waret and governed by carve up administrators.[26] Administrative documents and private stele betoken a proliferation of new bureaucratic titles around this time, which have been taken as bear witness of a larger central government.[77] Governance of the royal residence was moved into a separate division of authorities.[26] The military was placed nether the control of a chief general.[26] However, it is possible that these titles and positions were much older, and merely were not recorded on funerary stele due to religious conventions.[77]

Provincial regime [edit]

Decentralization during the First Intermediate Period left the individual Egyptian provinces, or Nomes, under the control of powerful families who held the hereditary title of Nifty Chief of the Nome, or Nomarch.[78] This position developed during the 5th and Sixth Dynasties, when the various powers of Old Kingdom provincial officials began to exist exercised by a single individual.[78] At roughly this time, the provincial aristocracy began edifice elaborate tombs for themselves, which have been taken every bit testify of the wealth and power which these rulers had acquired equally nomarchs.[78] Past the end of the Get-go Intermediate Menses, some nomarchs ruled their nomes equally minor potentates, such as the nomarch Nehry of Hermopolis, who dated inscriptions past his own regnal year.[75]

When the Eleventh Dynasty came to power, it was necessary to subdue the power of the nomarchs if Egypt was to be reunified under a central government. The first major steps towards that cease took identify under Amenemhet I. Amenemhet fabricated the city, not the nome, the eye of administration, and simply the haty-a, or mayor, of the larger cities would be permitted to carry the championship of nomarch.[26] The title of nomarch continued to be used until the reign of Senusret III,[26] as did the elaborate tombs indicative of their ability, after which they suddenly disappeared.[79] This has been interpreted several ways. Traditionally, it has been believed that Senusret III took some activeness to suppress the nomarch families during his reign.[80] Recently, other interpretations have been proposed. Detlef Franke has argued that Senusret Ii adopted a policy of educating the sons of nomarchs in the upper-case letter and appointing them to regime posts. In this way, many provincial families may have been bled dry of scions.[26] As well, while the championship of Peachy Overlord of the Nome disappeared, other distinctive titles of the nomarchs remained. During the First Intermediate Catamenia, individuals holding the title of Great Overlord also oft held the championship of Overseer of Priests. [81] In the belatedly Center Kingdom, at that place existed families property the titles of mayor and overseer of priests as hereditary possessions.[79] Therefore, it has been argued that the swell nomarch families were never subdued, but were merely absorbed into the pharaonic assistants of the land.[79] While information technology is true that the large tombs indicative of nomarchs disappear at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, grand royal tombs also disappear soon thereafter due to general instability surrounding the decline of the Middle Kingdom.[79]

Agriculture and climate [edit]

It was I who brought along grain, the grain god loved me,

the Nile adored me from his every source;

1 did not hunger during my years, did not thirst;

they sat content with all my deeds, remembering me fondly;

and I set each thing firmly in its identify. [82]

extract from the Instructions of Amenemhat

Throughout the history of ancient Egypt, the annual inundation of the Nile River was relied upon to fertilize the land surrounding it. This was essential for agriculture and food product. At that place is evidence that the collapse of the previous Onetime Kingdom may have been due in part to low flood levels, resulting in dearth.[83] This tendency appears to have been reversed during the early years of the Centre Kingdom, with relatively high water levels recorded for much of this era, with an average inundation of 19 meters in a higher place its not-flood levels.[84] The years of repeated high overflowing levels correspond to the most prosperous menstruum of the Middle Kingdom, which occurred during the reign of Amenemhat 3.[85] This seems to be confirmed in some of the literature of the period, such as in the Instructions of Amenemhat, where the rex tells his son how agriculture prospered under his reign.[82]

Art [edit]

After the reunification of Egypt in the Middle Kingdom, the kings of the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties were able to plough their focus back to art. In the Eleventh Dynasty, the kings had their monuments fabricated in a manner influenced by the Memphite models of the Fifth and early on Sixth Dynasty. During this time, the pre-unification Theban relief style all but disappeared. These changes had an ideological purpose, as the Eleventh Dynasty kings were establishing a centralized state after the First Intermediate Period, and returning to the political ethics of the Old Kingdom.[86] In the early 12th Dynasty, the artwork had a uniformity of fashion due to the influence of the royal workshops. Information technology was at this point that the quality of artistic production for the elite members of gild reached a high bespeak that was never surpassed, although it was equaled in other periods.[87] Egypt prospered in the late Twelfth Dynasty, and this was reflected in the quality of the materials used for royal and private monuments.

The kings of the 12th Dynasty were buried in pyramid complexes based on those of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.[88] In the Old Kingdom, these were made of rock bricks, just the Centre Kingdom kings chose to have theirs made of mud bricks and finished with a casing of Tura limestone.[89] Private tombs, such as those institute in Thebes, usually consisted of a long passage cut into rock, with a small chamber at the end. These tended to accept piddling or no ornament.[90] Stone box sarcophagi with both flat and vaulted lids were manufactured in the Middle Kingdom, as a continuation of the Old Kingdom tradition. The motifs on these were more than varied and of higher artistic quality than that of any sarcophagi produced before and after the Centre Kingdom.[91] Additionally, funerary stelae adult in regard to images and iconography. They connected to prove the deceased seated in front end of a tabular array of offerings, and began to include the deceased's wife and other family unit members.[92]

Towards the cease of the Centre Kingdom, there was a modify to the art pieces placed in non-royal tombs. The corporeality of wooden tomb models decreased drastically, and they were replaced by small faience models of food. Magic wands and rods, models of protective animals, and fertility figures began to be buried with the expressionless.[93] Additionally, the number of statues and funerary stelae increased, only their quality decreased. In the tardily Twelfth Dynasty, coffins with interior decorations became rare, and the decorations on the exterior became more elaborate. The rishi-coffin fabricated its first appearance during this fourth dimension. Made of wood or cartonnage, the coffin was in the shape of a body wrapped in linen, wearing a beaded neckband and a funerary mask.[94]

There were also changes to the art course of stelae in the Eye Kingdom. During this time, round-topped stelae adult out of the rectangular form of previous periods. Many examples of both of these types come from this period;[95] excavation at Abydos yielded over 2000 individual stelae, ranging from excellent works to crude objects, although very few belonged to the elite.[96] Additionally, classic royal commemorative stelae were first establish in this period. These took the form of a round-topped stelae, and they were used to mark boundaries. For case, Senusret Three used them to mark the boundary betwixt Egypt and Nubia.[95] Considering of the prosperity of this flow, the lower elite were able to commission statues and stelae for themselves, although these were of poorer creative quality.[97] Those who commissioned non-royal stelae had the ultimate goal of eternal existence. This goal was communicated with the specific placement of information on the stone slabs similar to purple stelae (the owner'southward image, offering formula, inscriptions of names, lineage and titles).[98]

Statuary [edit]

In the first one-half of the Twelfth Dynasty, proportions of the human being figure returned to the traditional Memphite mode of the Fifth and early Sixth Dynasties.[99] Male figures had broad shoulders, a low small of the back, and thick muscular limbs. Females had slender figures, a higher small-scale of the back and no musculature.[99] In this menstruation, sketches for the product of statues and reliefs were laid out on a squared grid, a new guide organization. Since this system contained a greater number of lines, it allowed more body parts to exist marked. Standing figures were composed of eighteen squares from the feet to the hairline. Seated figures were fabricated of fourteen squares between their feet and hairline, accounting for the horizontal thigh and knee.[100] The black granite seated statue of king Amenemhat Three to the right, above is a perfect example of male proportions and the squared grid organization at this period.[101] Most regal statues, such equally this one, would serve as representations of the king'due south ability.[102]

The quality of Egyptian bronze reached its peak in the Middle Kingdom.[103] Royal statues combined both elegance and strength in a fashion that was seldom seen after this flow.[104] A popular class of statuary during this time was that of the sphinx. During this period, sphinxes appeared in pairs, and were recumbent, with homo faces, and a panthera leo'due south mane and ears. An case would be the diorite sphinx of Senusret III.[103]

Ane of the innovations in sculpture that occurred during the Middle Kingdom was the cake statue, which would continue to be popular through to the Ptolemaic Kingdom nearly 2,000 years later.[105] Block statues consist of a man squatting with his knees drawn up to his chest and his arms folded on acme his knees. Often, these men are wearing a "broad cloak" that reduces the body of the figure to a simple cake-like shape.[106] The surface of the garment or "wide cloak" allowed space for inscriptions.[87] Virtually of the detail is reserved for the head of the individual being depicted. In some instances the modeling of the limbs has been retained by the sculptor.[107] There are 2 basic types of block statues: ones with the feet completely covered by the cloak and ones with the feet uncovered.[108]

This statue to the right represents a woman from the top echelon of order and demonstrates characteristics of Middle Kingdom art. The heavy tripartite wig frames the broad face and passes backside the ears, thus giving the impression of forcing them forward. They are large in keeping with the ancient Egyptian ideal of beauty; the same ideal required small breasts, and likewise in this respect the sculpture is no exception. Whereas the natural curve of the eyebrows dips towards the root of the olfactory organ, the artificial eyebrows in low relief are absolutely straight above the inner corners of the optics, a characteristic which places the bust early in the Twelfth Dynasty. Around 1900 BC these bogus eyebrows began to follow the natural curve and dip toward the nose.[109]

In the later Twelfth Dynasty, proportions of the human figure changed. These changes survived through the Thirteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties. Male figures had smaller heads in proportion the rest of the trunk, narrow shoulders and waists, a high pocket-sized of the back, and no muscled limbs. Female figures had these proportions more to an extreme with narrower shoulders and waists, slender limbs and a college small of the back in order to continue a distinction between male person and female measurements.[110]

Literature [edit]

Richard B. Parkinson and Ludwig D. Morenz write that ancient Egyptian literature—narrowly divers as belles-lettres ("beautiful writing")—were not recorded in written form until the early Twelfth Dynasty.[111] Onetime Kingdom texts served mainly to maintain the divine cults, preserve souls in the afterlife, and document accounts for practical uses in daily life. It was not until the Eye Kingdom that texts were written for the purpose of entertainment and intellectual curiosity.[112] Parkinson and Morenz also speculate that written works of the Middle Kingdom were transcriptions of the oral literature of the Old Kingdom.[113] It is known that some oral verse was preserved in after writing; for instance, litter-bearers' songs were preserved every bit written verses in tomb inscriptions of the Old Kingdom.[112]

It is too thought that the growth of the middle class and a growth in the number of scribes needed for the expanded bureaucracy under Senusret II helped spur the development of Middle Kingdom literature.[63] Afterwards aboriginal Egyptians considered the literature from this time as "classic".[63] Stories such as the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and the Story of Sinuhe were composed during this menstruum, and were popular plenty to be widely copied later.[63] Many philosophical works were too created at this time, including the Dispute between a man and his Ba where an unhappy man converses with his soul, The Satire of the Trades in which the role of the scribe is praised above all other jobs, and the magic tales supposedly told to the One-time Kingdom pharaoh Khufu in the Westcar Papyrus.[63]

Pharaohs of the Twelfth through Eighteenth Dynasty are credited with preserving some of the most interesting of Egyptian papyri:

- 1950 BC: Akhmim Wooden Tablet

- 1950 BC: Heqanakht papyri

- 1800 BC: Berlin papyrus 6619

- 1800 BC: Moscow Mathematical Papyrus

- 1650 BC: Rhind Mathematical Papyrus

- 1600 BC: Edwin Smith papyrus

- 1550 BC: Ebers papyrus

References [edit]

- ^ Schneider, Thomas (27 August 2008). "Periodizing Egyptian History: Manetho, Convention, and Beyond". In Klaus-Peter Adam (ed.). Historiographie in der Antike. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 181–197. ISBN978-3-11-020672-2.

- ^ David, Rosalie (2002). Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books. p. 156

- ^ a b Grimal. (1988) p. 156

- ^ a b Grimal. (1988) p. 155

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 149

- ^ Habachi. (1963) pp. xvi–52

- ^ a b c Grimal. (1988) p. 157

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 151

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 156

- ^ a b c Redford. (1992) p. 71.

- ^ Gardiner. (1964) p. 124.

- ^ Redford. (1992) p. 72.

- ^ a b c Gardiner. (1964) p. 125.

- ^ Redford. (1992) p.74

- ^ "Guardian Figure". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ p5. 'The Collins Encyclopedia of Military History', (4th edition, 1993), Dupuy & Dupuy.

- ^ Arnold. (1991) p. 20.

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 148

- ^ Arnold. (1991) p. xiv.

- ^ a b Shaw. (2000) p. 158

- ^ Grimal. (1988) p. 159

- ^ Gardiner. (1964) p. 128.

- ^ Grimal. (1988) p. 160

- ^ a b Gardiner. (1964) p. 129.

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 160

- ^ a b c d due east f thousand h Shaw. (2000) p. 175

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 162

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 161

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell (July 19, 1994). p. 164.

- ^ a b c Grimal. (1988) p. 165

- ^ Murnane. (1977) p. 5.

- ^ Mieroop, Marc Van De (2010). A History of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 131. ISBN978-1-4051-6070-4.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Aboriginal Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN978-1-118-89611-2.

- ^ Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep Two at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 1:3. S2CID 199601200.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Mag". www.archæology.org.

- ^ a b c Shaw. (2000) p. 163

- ^ Murnane. (1977) p. 7.

- ^ a b Shaw. (2000) p. 164

- ^ Gardiner. (1964) p. 138.

- ^ Grimal. (1988) p. 166

- ^ a b c d Shaw. (2000) p. 166

- ^ Gardiner. (1964) p. 136.

- ^ Gardiner. (1964) p. 135.

- ^ Redford. (1992) p. 76

- ^ Bar, South.; Kahn, D.; Shirley, J.J. (2011). Egypt, Canaan and State of israel: History, Imperialism, Credo and Literature (Culture and History of the Ancient Most Eastward). BRILL. p. 198.

- ^ The Eye Kingdom (1938–c. 1630 BCE) and the 2d Intermediate period (c. 1630–1540 BCE)

- ^ Gee, John (2004). "Disregarded Prove for Sesostris 3's Strange Policy". Journal of the American Research Middle in Arab republic of egypt: 23–31.

- ^ "Byblos". Britannica.

- ^ Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer lexicon of the Bible. Mercer University Press. pp. 124–. ISBN978-0-86554-373-7 . Retrieved eight July 2011.

- ^ Grajetzki, Wolfram (2014). "Tomb 197 at Abydos, Further Prove for Long Distance Trade in the Centre Kingdom". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 24: 159–170. doi:10.1553/s159. JSTOR 43553796.

- ^ Stevenson, Alice (2015). Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections. UCL Printing. p. 54. ISBN9781910634042.

- ^ Hayes. (1953) p. 32

- ^ Shaw and Nicholson. (1995) p. 260

- ^ Aldred. (1987) p.129

- ^ Wegner. (1996) p. 250

- ^ Wegner. (1996) p. 260

- ^ a b Grimal. (1988) p. 170

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 60

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 168

- ^ a b Shaw. (2000) p. 169

- ^ Shaw. (2000) p. 170

- ^ a b Grimal. (1988) p. 171

- ^ a b c d eastward Shaw. (2000) p. 171

- ^ Grand.S.B. Ryholt: The Political Situation in Arab republic of egypt during the 2d Intermediate Flow, c.1800–1550 BC, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997

- ^ Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC, Stacey International, ISBN 978-i-905299-37-9, 2008

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 66

- ^ Grimal. (1988) p. 183

- ^ a b c Grajetzki. (2006) p. 64

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 65

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 71

- ^ a b c Shaw. (2000) p. 172

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 72

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 74

- ^ Grajetzki. (2006) p. 75

- ^ a b c d e Shaw. (2000) p. 174

- ^ a b c d Grajetzki. (2006) p. 21

- ^ a b Richards. (2005) p. 7

- ^ a b c Trigger, Kemp, O'Connor, and Lloyd. (1983) p. 108

- ^ a b c d Trigger, Kemp, O'Connor, and Lloyd. (1983) p. 112

- ^ Grimal. (1988) p. 167

- ^ Trigger, Kemp, O'Connor, and Lloyd. (1983) p. 109

- ^ a b Foster. (2001) p. 88

- ^ Bell. (1975) p. 227

- ^ Bell. (1975) p. 230

- ^ Bell. (1975) p. 263

- ^ Robins, Gay (2008). The Fine art of Aboriginal Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. ninety. ISBN9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

- ^ a b Robins (2008), p. 109.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 96.

- ^ Watson, Philip J.; Gendrop, Paul; Stillman, Damie (2003). "Pyramid | Grove Art". doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t070190. ISBN978-one-884446-05-four . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ "Thebes (i) | Grove Fine art". doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t084413. ISBN978-one-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ "Sarcophagus | Grove Fine art". doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t075996. ISBN978-1-884446-05-four . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 102.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 114.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 115.

- ^ a b Collon, Dominique; Strudwick, Nigel; Lyttleton, Margaret; Wiedehage, Peter; Blair, Sheila S.; Benson, Elizabeth P. (2003). "Stele | Grove Art". doi:x.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t081249. ISBN978-i-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ "Abydos | Grove Art". doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.commodity.t000298. ISBN978-i-884446-05-four . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 110.

- ^ Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kei (2015). Ancient Egypt transformed: the Center Kingdom. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 36. ISBN9781588395641. OCLC 909251373.

- ^ a b Robins (2008), pp. 106, 107.

- ^ Robins (2008), pp. 107, 108.

- ^ "Statue of Amenemhat Three". hermitagemuseum . Retrieved half-dozen Dec 2018.

- ^ Robins (2008), pp. 112, 113.

- ^ a b Boddens-Hosang, F. J. E.; d'Albiac, Carole (2003). "Sphinx | Grove Art". doi:ten.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t080560. ISBN978-1-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ Russmann, Edna R. (2003). "Taharqa | Grove Fine art". doi:x.1093/gao/9781884446054.commodity.t083009. ISBN978-ane-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 2018-12-03 .

- ^ Teeter. (1994) p. 27

- ^ Bothmer, 94.

- ^ Shaw, "Block Statue".

- ^ Late Menstruation, 4–v.

- ^ Bothmer, Bernard (1974). Cursory Guide to the Department of Egyptian and Classical Fine art. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum. p. 36.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 118.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–fifty, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102; see also Simpson 1972, pp. three–6 and Erman 2005, pp. xxiv–xxv.

- ^ a b Morenz 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–50, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102.

Bibliography [edit]

- Aldred, Cyril (1987). The Egyptians. Thames and Hudson.

- Arnold, Dorothea (1991). "Amenemhet I and the Early 12th Dynasty at Thebes". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 26: 5–48. doi:10.2307/1512902. JSTOR 1512902. S2CID 191398579.

- Bell, Barbara (1975). "Climate and the History of Egypt: The Middle Kingdom". American Journal of Archaeology. Archaeological Found of America. 79 (3): 223–269. doi:10.2307/503481. JSTOR 503481. S2CID 192999731.

- Erman, Adolf (2005). Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Collection of Poems, Narratives and Manuals of Instructions from the Third and Second Millennia BC. Translated by Aylward Grand. Blackman. New York: Kegan Paul. ISBN0-7103-0964-3.

- Foster, John L. (2001). Aboriginal Egyptian Literature: An Anthology. University of Texas Press. ISBN0-292-72527-2.

- Gardiner, Alan (1964). Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford Academy Press.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2006). The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. ISBN0-7156-3435-6.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1988). A History of Ancient Egypt. Librairie Arthéme Fayard.

- Habachi, Labib (1963). "King Nebhepetre Menthuhotep: his monuments, place in history, deification and unusual representations in form of gods". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. nineteen: 16–52.

- Hayes, William (1953). "Notes on the Authorities of Egypt in the Late Heart Kingdom". Journal of Nigh Eastern Studies. 12: 31–39. doi:10.1086/371108. S2CID 162220262.

- Morenz, Ludwid D. (2003), "Literature every bit a Construction of the Past in the Heart Kingdom", in Tait, John W. (ed.), 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt's View of Its By, translated by Martin Worthington, London: Academy Higher London, Establish of Archæology, an banner of Cavendish Publishing Express, pp. 101–118, ISBNi-84472-007-1

- Murnane, William J. (1977). Ancient Egyptian Coregencies. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 40. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN0-918986-03-6.

- Parkinson, R. B. (2002). Poesy and Civilisation in Eye Kingdom Arab republic of egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection. London: Continuum. ISBN0-8264-5637-five.

- Redford, Donald (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times . Princeton Academy Press. ISBN0-691-00086-7.

- Richards, Janet (2005). Society and Decease in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-84033-iii.

- Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul (1995). The Lexicon of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson.

- Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford history of ancient Egypt . Oxford University Press. ISBN0-19-280458-8.

- Simpson, William Kelly (1972). The Literature of Ancient Arab republic of egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry. translations by R.O. Faulkner, Edward F. Wente, Jr., and William Kelly Simpson. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-01482-1.

- Teeter, Emily (1994). "Egyptian Art". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. The Art Establish of Chicago. 20 (ane): 14–31. doi:10.2307/4112949. JSTOR 4112949.

- Trigger, B.; Kemp, Barry; O'Connor, David; Lloyd, Alan (1983). Ancient Egypt: A Social History. Cambridge University Press.

- Wegner, Josef (1996). "The Nature and Chronology of the Senwosret Iii–Amenemhat Three Regnal Succession: Some Considerations Based on New Bear witness from the Mortuary Temple of Senwosret III at Abydos". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 55 (4): 249–279. doi:x.1086/373863. S2CID 161869330.

Farther reading [edit]

- Allen, James P. Middle Egyptian Literature: Eight Literary Works of the Eye Kingdom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Bourriau, Janine. Pharaohs and Mortals: Egyptian Art in the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge, Uk: Fitzwilliam Museum, 1988.

- Grajetzki, Wolfgang. The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Social club. Bristol, UK: Golden House, 2006.

- Kemp, Barry J. Ancient Arab republic of egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. 2d ed. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Oppenheim, Adela, Dieter Arnold, and Kei Yamamoto. Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Eye Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 2015.

- Parkinson, Richard B. Voices From Aboriginal Egypt: An Anthology of Eye Kingdom Writings. Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- --. Verse and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection. London: Continuum, 2002.

- Szpakowska, Kasia. Daily Life in Aboriginal Arab republic of egypt. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

- Wendrich, Willeke, ed. Egyptian Archæology. Chichester, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Kingdom_of_Egypt

Posted by: fernandezberstionshe1988.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Is One Of The Greatest Changes That Took Place During The Middle Kingdom?"

Post a Comment